- February 2023

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 61-2023

Eviction is not an isolated incident. The causes of housing loss are complex and can have compounding negative consequences, particularly for low-income families. A recent working paper—Eviction and Poverty in American Cities by Robert Collinson, John Eric Humphries, Nick Mader, Davin Reed, Daniel Tannenbaum and Winnie van Dijk—explores the precursors and effects of eviction and offers insights for potential policy interventions.[1]

Adverse events such as unemployment and health challenges often lead to economic distress for tenants. Such distress can lead to the unpaid or overdue rent that triggers an eviction case filing. By the time a landlord files a case in housing court, tenants have experienced drops in earnings, loss of employment, and mounting debt. Other risk factors for eviction include episodes of housing instability, accumulation of overdue bills, and health challenges leading to a hospital visit.[2] These risk factors can be particularly difficult to overcome for people belonging to groups already systematically marginalized in the United States, including Black families and women with children.

A common obstacle for eviction-related research is linking data on households facing eviction to data capturing the circumstances following eviction. Another common challenge is establishing causal links between an eviction case filing and related sources of distress, including physical and mental health troubles, loss of earnings, worsening financial health, or the dissolution of a relationship. Using data drawn from housing court records in New York City and Cook County, IL (which includes Chicago) and a wide range of administrative data, the authors created a novel dataset to document and characterize aspects of tenants’ lives commonly preceding eviction and then track those characteristics among evicted tenants for the years following a case. The research team uses the fact that eviction cases are randomly assigned to judges to compare the outcomes of cases assigned to strict and lenient judges to learn about the causal effects of eviction.

Social Costs of Eviction

Eviction causes significant increases in homelessness and residential mobility (i.e., housing instability). The authors find evidence that these effects can last 12 to 24 months or longer after an eviction case is filed. In the year following an eviction order, the probability of tenants living at a different address increases by about 8 percentage points, on average, and increases the probability of staying in an emergency shelter by 3.4 percentage points, or more than 300% the rate for non-evicted tenants in the same neighborhoods. These effects generally persist through the second year after a case filing.

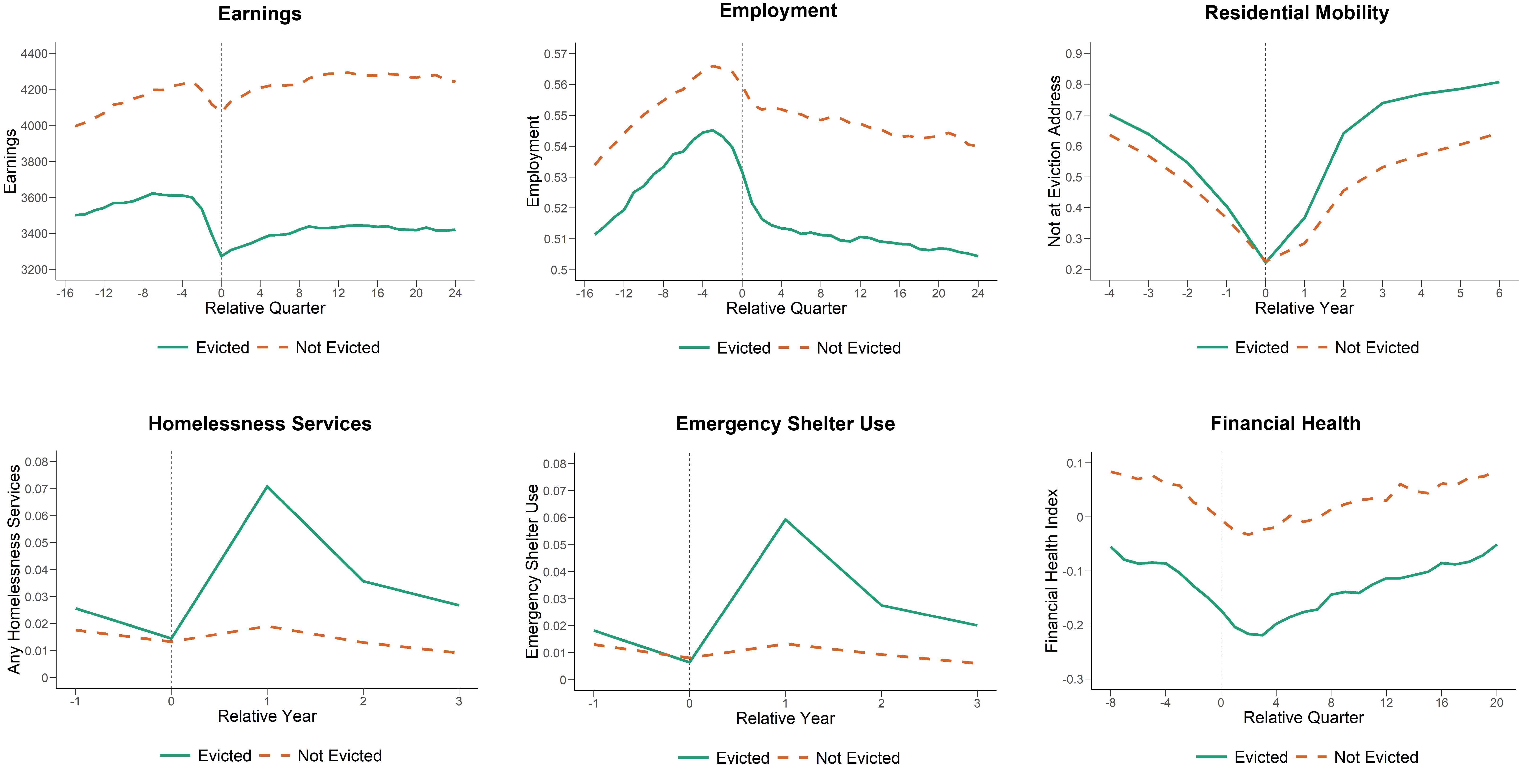

During periods of post-eviction homelessness or housing instability, employment and earnings also declined significantly, as seen in Figure 1. Eviction’s effects on labor market participation tend to persist into the second year following a case filing. Such effects are particularly pronounced for female and Black tenants—populations already facing increased residential mobility and interactions with homelessness services (e.g., homeless shelters, etc.). These patterns align with ethnographic research demonstrating eviction’s disproportionate impacts on women and Black families facing systemic discrimination when seeking rental options.[3] The authors also find evidence of negative impacts on financial health and access to credit, which tended to last beyond initial experiences of housing instability and homelessness.

Source: Collinson et al. 2022.

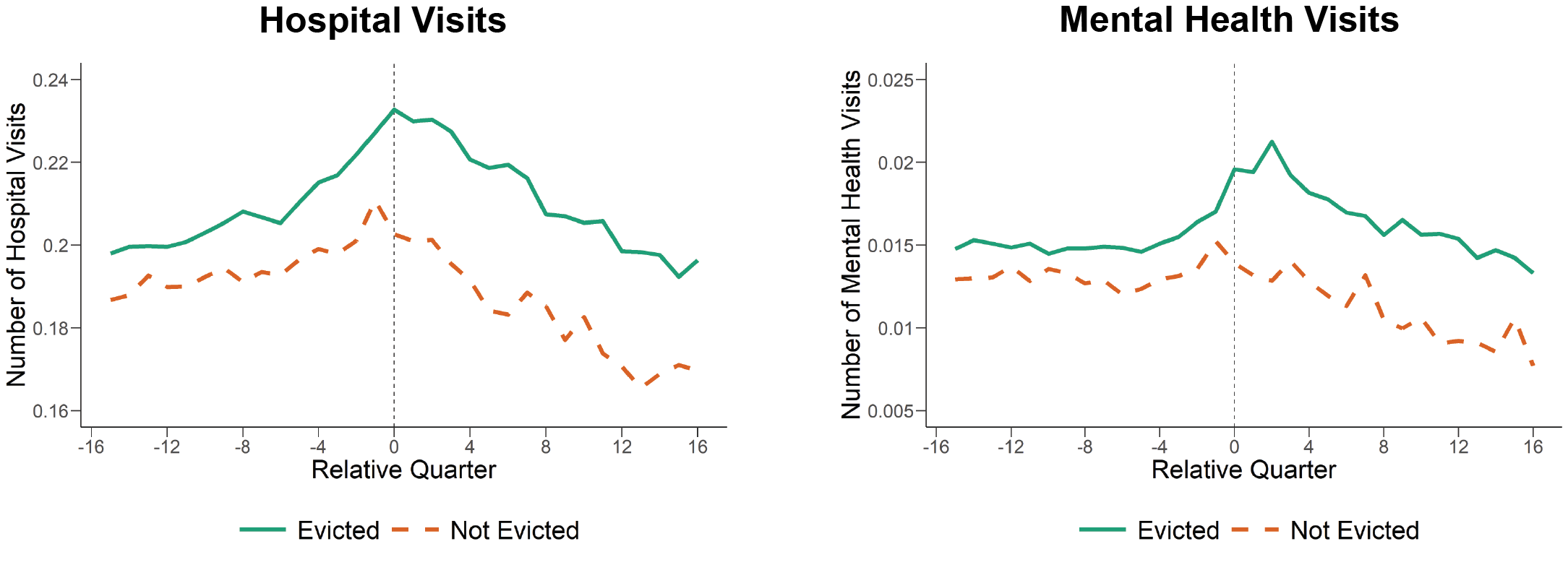

The data suggest that physical and mental health also take a hit. Among the study sample, hospital visits often precede an eviction filing and visits for mental health-related conditions jumped by more than 130 percent following evictions. These results align with other evidence of eviction’s negative physical and mental health impacts on children, including increases in childhood hunger (i.e., food insecurity).[4] Eviction prevention efforts can therefore be cost-effective means of reducing childhood deprivation while safeguarding cognitive development.[5]

Source: Collinson et al. 2022.

Policy Implications

Several implications emerge for policies such as: the availability of emergency rental assistance, legal aid for tenants faced with eviction, extended notice periods, and, importantly, creating more lenient eviction proceedings toward tenants. Of course, such policies—and potential reforms—would also affect property owners and their interests regarding rental unit supply, rental rates, and tenant screening practices.

As the recent Biden-Harris federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness asserts, eviction prevention is a key concern.[6] Measures under consideration by the current administration are reported to include sealing eviction records, creating standardized rental leases, and “promoting a right to counsel for tenants facing off with landlords in housing court.”[7] Given the high social costs of homelessness,[8] if housing courts have the means to seek and implement tenant-oriented alternatives—thus disrupting the spiral of negative effects preceding and following eviction—prevention can reduce downstream costs significantly for households and society.

Existing social insurance policies or self-insurance may also be inadequate, under-serving at-risk tenants—including groups such as Black renters and female tenants—who are over-represented in eviction proceedings. Policies adopting a “targeted universalism”[9] approach—as recommended in the federal “All In” strategic plan—may be particularly helpful in addressing such disparities by adopting overall reduction goals aligned with “targeted and tailored solutions based on the structures, cultures, and geographies of certain groups.”[10] Such approaches recognize that while homelessness prevention—through reduced evictions, for example—may be a universal goal, the means to those ends will differ depending on the groups targeted by prevention efforts.

Eviction prevention can be cost-effective in that it greatly reduces downstream negative effects. Given that unanticipated hospital visits are a risk factor, expansions of the ACA Marketplace subsidies, for example, can significantly reduce eviction filing rates[11] while Medicaid expansions have been associated with reduced county-level filing and eviction rates.[12] Other risk factors or household characteristics that may benefit from targeted policy attention include programs that help tenants with larger families, households experiencing prior job loss, high rates of crime and eviction in at-risk neighborhoods, as well as those households facing network disadvantage (i.e., the density of social marginalization within tenants’ kin networks).[13] From a public health perspective, when the federal eviction moratorium—established in response to the global health pandemic—was allowed to expire, results included both a surge in evictions as well as increased COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates.[14]

Summary

The evidence on primary causes and consequences of eviction demonstrates the lasting effects on renters’ earnings, probability of homelessness, and domains of health including physical, psychological, and financial. Eviction’s direct effects of leading to increased homelessness and reduced earnings in the 24 months following a case filing further exacerbate social and structural inequalities. Negative effects on financial health are even longer lasting. In short, eviction acts as a catalyst for economic distress, particularly for members of already marginalized communities such as Black families and women. Further research is needed to determine whether policies aimed at eviction prevention can be cost effective and may significantly reduce upheaval for tenants—especially those with children—and the multiple related costs for society.

[1]Collinson, R., Humphries, J. E., Mader, N. S., Reed, D. K., Tannenbaum, D. I., van Dijk, W. (2022, August). Eviction and poverty in American cities. NBER Working Paper 30382.

[2]Desmond, M. (2012). Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 118(1), 88–133. https://doi.org/10.1086/666082. Desmond, M., An, W., Winkler, R., & Ferriss, T. (2013). Evicting Children. Social Forces, 92(1), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot047. Desmond, M. & Gershenson, C. (2016). Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor. Social Problems, 63, 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spv025.

[3]Bayer, P., Casey, M., Ferreira, F. & McMillan, R. (2017). Racial and Ethnic Price Differentials in the Housing Market. Journal of Urban Economics, 102, 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2017.07.004. Christiansen, P. & Timmins, C. (2019). Sorting or steering: Experimental evidence on the effects of housing discrimination on location choice. NBER Working Paper 24826.

[4]Leifheit, K. M., Schwartz, G. L., Pollack, C. E., Black M. M., Edin, K. J., Althoff, K. N., & Jennings, J. M. (2020, August). Eviction in early childhood and neighborhood poverty, food security, and obesity in later childhood and adolescence: Evidence from a longitudinal birth cohort. SSM – Population Health, 11, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100575.

[5]Schwartz, G. L., Leifheit, K. M., Chen, J. T., Arcaya, M. C., & Berkman, L. F. (2022, January). Childhood eviction and cognitive development: Developmental timing-specific associations in an urban birth cohort. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114544.

[6]U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). (2022, Dec.). All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.

[7]Capps, K. (2023, Jan. 18). The White House is considering broad actions to expand tenant protections. Bloomberg CityLab.

[8]Evans, W. N., Philips, D. C., & Ruffini, K. J. (2019). Reducing and Preventing Homelessness: A Review of the Evidence and Charting a Research Agenda. NBER Working Paper 26232.

[9]powell, j. a., Menendian, S. & Ake, W. (2019, May). Targeted Universalism: Policy & Practice. Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley.

[10]USICH. (2022, December). All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, p. 25.

[11]Gallagher, E. A., Gopalan, R. & Grinstein-Weiss, M. (2019). The Effects of Health Insurance on Home Payment Delinquency: Evidence from the ACA Marketplace Subsidies. Journal of Public Economics, 172, 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.12.007.

[12]Zewde, N., Eliason, E., Allen, H., & Gross, T. (2019). The Effects of the ACA Medicaid Expansion on Nationwide Home Evictions and Eviction-Court Initiations: United States. Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1379–1383. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305230.

[13]Desmond, M. & Gershenson, C. (2016). Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor. Social Problems, 63, 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spv025.

[14]Leifheit, K. M., Linton, S. L., Raifman, J., Schwartz, G., Benfer, E., Zimmerman, F. J., & Pollack, C. (2020, Nov. 30). Expiring Eviction Moratoriums and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3739576.

Categories

Eviction & Foreclosure, Gender Inequality, Homelessness, Housing, Inequality & Mobility, Racial/Ethnic Inequality

Tags

Administrative Data, Affordable Care Act (ACA), Quantitative Research, Race/Ethnicity, Urban, Women