- November 29 2021

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 57-2021

Over the past four decades, many workers in hourly front-line jobs in the retail and food service sectors have been subject to low pay and few basic benefits.[1] More recently, those challenges have been compounded by an increase in what is termed “temporal precarity,” or the lack of a stable and predictable work schedule. Employers in these sectors increasingly implement “just-in-time scheduling,” which shifts risks away from the employer and onto the employees. This can play out in a variety of ways, including:

- lack of a regular number of hours per week;

- absence of a consistent schedule of days worked, or time of day of shifts;

- short notice of scheduled shifts, sometimes less than 48 hours in advance;

- last-minute changes to or cancellation of scheduled shifts;

- early dismissal from a scheduled shift if demand is less than anticipated; and

- requirements to be on-call but not compensated if not called in to work.

At the most basic level, work schedule unpredictability and instability can lead to income volatility, with the amount of income varying from month to month and even week to week. This is out of step with the typical monthly schedules on which people are expected to pay for regular expenses like rent, utilities, or car payments.

According to the 2016 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) conducted by the Federal Reserve Board, one-third of U.S. households reported that their income fluctuates monthly. But those households are not evenly distributed across the income spectrum. A sample of related findings[2] shows that lower-income households experience month-to-month income volatility more often than middle- or higher-income households, and households with children in the lowest 10% of the income distribution are three times as likely to experience such precarity than households in the top 10%. In addition, Chase banking data analyzed by researchers revealed that nearly three-quarters of households in the lowest 20% had to manage monthly income fluctuations of 30% or more.[3]

Unpredictable work schedules also create or contribute to a host of other challenges for low-income individuals and households. For example, several safety net programs targeted to support this population (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and childcare subsidies) assess eligibility based on income and work hours, and participants are subject to frequent recertification requirements. When hours and income are unpredictable, it can be difficult to maintain needed benefits and to receive an accurate and adequate amount of support.

New Insights into The Impacts of Routine Schedule Unpredictability

In a recent paper in the journal Social Forces,[4] researchers Daniel Schneider and Kristen Harknett studied the impact of temporal precarity on material hardships among low-income workers. Unpredictable work schedules make it difficult for low-wage and entry-level workers to provide for basic needs. These types of work schedules increase the risk of living in poverty and can contribute to declines in mental and physical health. The material hardships they examine include:

- Hunger hardship, which includes going without food, or utilizing free food or meal services;

- Residential hardship, which includes doubling up with friends or family or staying in a shelter or location not designated for habitation, like a car or in an abandoned building;

- Medical hardship, which results when the respondent or someone in their family forgoes medical care because of the cost; and

- Utility hardship, which includes the inability to pay basic utility bills (e.g., gas, oil, electric) in full or on time.

Using information collected by The Shift Project from over 37,000 hourly workers employed at 127 of the nation’s largest retail and food service companies, Schneider and Harknett establish the association between workers’ exposure to unpredictable work scheduling and the number and types of material hardships that they experienced.

Types of work shift unpredictability measured here included how much advanced notice workers received for their schedules (e.g., a range between 0-2 days or up to 2 weeks or more), whether they were required to be “on-call,” work shift cancellations, and work short-notice changes in shift time or day. The authors found that 80% of service sectors workers were subject to one or more types of schedule unpredictability. About 37% of workers reported just one type, 40% experienced two or three types, and 3% experiencing all four types of unpredictability.

About two-thirds of the respondents reported less than two weeks’ notice of their work schedule, and a slightly higher percentage reported a last-minute schedule change within the previous month. The workers in the sample also experienced swings in the number of hours that they worked. Overall, the average worker saw a difference of 36% between the weeks with the least and most hours worked in the previous month.

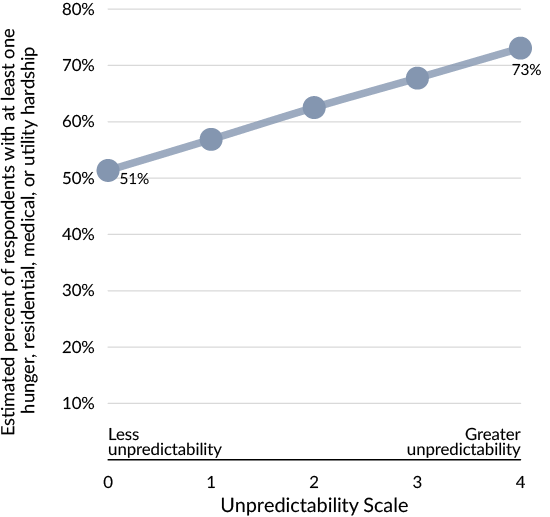

Nearly two-thirds of respondents reported experiencing at least one type of material hardship. Of those, 18% experienced one type, 15% experienced two, 12% experienced three, and 14% experienced four or more. Utility hardship was the most common and was reported by 31% of respondents, with hunger hardship a close second at 30%. Medical hardship was reported by 25% of the workers surveyed, and residential hardship was reported by 16%.

Schneider and Harknett’s analysis provides valuable and nuanced insights into how specific types of schedule unpredictability contribute to material hardships for workers, and which types of unpredictability carry the most risk. Clear connections emerged between having more notice of one’s work schedule and a decreased risk of hunger hardship, for example. A similar connection is noted in terms of reducing residential, medical, and utility hardships.

Note: Unpredictability scale is the number of scheduling challenges respondents reported among less than two weeks’ notice for schedules, whether they were required to be “on-call,” work shift cancellations, or work short-notice changes in shift time or day.

Source: Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2021). Hard Times: Routine Schedule Unpredictability and Material Hardship among Service Sector Workers. Social Forces, 99(4), 1682–1709.

In examining these forms of schedule unpredictability (i.e., on-call shifts, shift cancellations, and shift timing changes), the evidence suggests that not all contribute equally to the likelihood of material hardship. Those who reported being subject to shift cancellations were the most likely to experience each of the four types of material hardship. As shift cancellation would likely contribute to income volatility, it is not surprising that those with the most volatile income were also most likely to experience any of these hardships.

It is important to note that even without experiencing schedule unpredictability, hourly workers in the retail and food service sectors often exist in perilous economic circumstances. For example, nearly a quarter of workers who reported no schedule unreliability in the previous month nonetheless experienced food hardship.

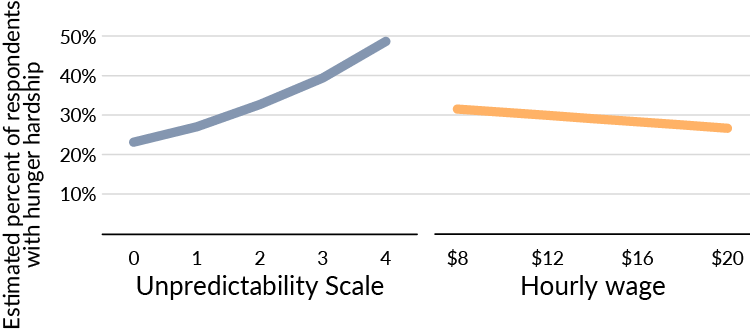

The research by Schneider and Harknett and others demonstrates that to address low wages without ensuring schedule stability will have limited success in improving worker well-being and economic mobility. Even after accounting for hourly wages, workers who reported the most schedule unpredictability were twice as likely to endure hunger hardship than those who reported no schedule unpredictability.

Policy Recommendations

The effects of unpredictable work scheduling as outlined above were firmly in place before the COVID-19 pandemic, and many workers facing temporal precarity found themselves thrust into the epicenter of a combined health and economic crisis. Many retail and other frontline workers were laid-off, while others were forced to work in close contact with the public, often in the absence of paid sick time or health benefits. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, half of the workers who provided information to The Shift Project experienced at least one instance of material hardship in the previous year.

The pandemic has put into sharp relief the essential nature of the work done by those employed in retail and food service and has also led to calls for better conditions for front-line workers.

Note: Unpredictability scale is the number of scheduling challenges respondents reported among less than two weeks’ notice for schedules, whether they were required to be “on-call,” work shift cancellations, or work short-notice changes in shift time or day.

Source: Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2021). Hard Times: Routine Schedule Unpredictability and Material Hardship among Service Sector Workers. Social Forces, 99(4), 1682–1709.

Conversations in the public sphere and among policymakers most often center on the need for increased wages, as seen by the many and various efforts to increase the federal and state-level minimum wage. But what the research conducted by Schneider and Harknett and others shows is that to address wages in isolation will not achieve the positive change that proponents hope for. Instead, those efforts would need to be paired with regulations to encourage more schedule predictability and rein in practices like “just-in-time scheduling.”

Examples of efforts to address schedule unpredictability through targeted policies include “secure scheduling” legislation mandating a longer lead time for workers to receive their schedules. Several cities and states now require employers to compensate employees when they are subject to schedule changes, cancellations, or on-call shifts and others are considering similar laws. At the same time, a few states have prohibited the implementation of secure scheduling legislation by any municipalities within their jurisdiction.

Research tracing the connections between secure schedules and important outcomes like hunger and other material hardships is an important reminder of what’s at stake in these policy debates. Policies that promote more stable and secure schedules have the potential to make an important difference to some fundamental measures of financial and social well-being for these essential workers.

Emeryville, CA

Chicago, IL

New York, NY

Seattle, WA

Philadelphia, PA

Arkansas

Georgia

Iowa

Indiana

Kansas

Michigan

Ohio

Tennessee

[1]Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22.

[2]Morris, P., Hill, H., Gennetian, L., Rodrigues, C., & Wolf, S. (2015). Income volatility in U.S. households with children: Another growing disparity between the rich and the poor? (Working Paper No. 1429-15). Institute for Research on Poverty.

[3]Farrell, D., & Greig, F. (2016, January). Paychecks, paydays, and the online platform economy. In Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association (Vol. 109, pp. 1–40).

[4]Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. Hard times: routine schedule unpredictability and material hardship among service sector workers. Social Forces, 99(4), June 2021, 1682–1709.

Categories

Employment, Financial Security, Food & Nutrition, Food Insecurity, Health, Health General, Housing, Housing General, Labor Market, Low-Wage Work, Means-Tested Programs