- October 15 2021

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 56-2021

Service disparities for people with autism

Family- and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES), as well as racial and ethnic minority status, are strongly related to disparities in access to quality autism care.[1] Children from low-SES households and racial and ethnic minority families in the United States are less likely to receive an autism diagnosis, and experience a later age of diagnosis, than higher SES and White families.[2] Since services to support people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are usually tied to a diagnosis, lag-time in diagnosis results in delayed access to treatment, leading to poorer long-term outcomes.[3] Lower-SES and racial and ethnic minority families also tend to find it more difficult to access services, report a greater number of unmet service needs, and experience a lower level of satisfaction with current services. Data also suggest that in adulthood, African American and low-income autistic adults are less likely to receive services than their White and middle- to high-income peers,[4] suggesting that racial and socioeconomic disparities significantly affect service access and use across the lifespan.

Research on service disparities for people with ASD highlights a range of factors influencing the likelihood of receiving an ASD diagnosis and accessing ASD treatment services. Structural and family-level barriers likely influence trends in reduced access to services among low-SES and racial and ethnic minority families. For example, the high cost of services, lack of health insurance, transportation difficulties, and inflexible work schedules can all act as structural barriers for low-SES families of children with ASD.[5] Similar barriers may also affect racial and ethnic minority families who are overrepresented among low-income U.S. American families overall.[6] Rural families of children with ASD also tend to find themselves living in service deserts, where they have greater difficulty accessing services due to transportation challenges and limited availability of trained physicians.[7]

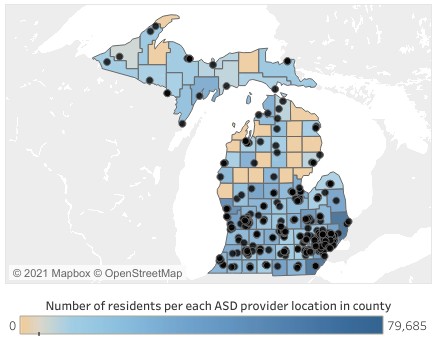

To answer questions about disparities across economic and racial lines, a research team led by Amy Drahota of Michigan State University used innovative geographic information systems (GIS) mapping techniques to better understand the distributions and correlations related to locations where individuals with ASD and their families can access services across the state of Michigan.[8] Figure 1, below, includes two interactive maps, one noting ASD service locations compared to poverty rates per Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) and a second comparing service locations to county-level population densities.

Service “deserts” or “oases” are, respectively, areas of low or high treatment service availability. Characterizing access to treatment services is particularly important given the rising rates of individuals diagnosed with ASD.[9] Drahota and colleagues—including Richard Sadler and Christopher Hippensteel of Michigan State University, Brooke Ingersoll of the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, and IRP Affiliate Lauren Bishop of the University of Wisconsin–Madison—evaluated factors of community-based ASD service access (i.e., “the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate health care services in situations of perceived need for care”[10]) for individuals with ASD in the geographically and socioeconomically diverse state of Michigan.

- Fewer service agencies will be located in less populated areas compared with more populated areas;

- Areas with low neighborhood SES will have fewer ASD services compared with neighborhoods with medium and high SES; and

- Areas with low SES and high population densities will have fewer available ASD services compared to areas with medium or high SES and high population densities.

Similar to work on classifying food deserts and oases, identifying disability-related service deserts or service oases can help practitioners, decisionmakers, and researchers understand gaps in services and make progress towards fulfilling unmet needs. Yet measuring service disparities using mapping technology such as GIS must be done strategically, paying special attention to population density, population demographics, and neighborhood-level SES, for example. It is important to examine service gaps with an eye toward enhancing equity for people on the autism spectrum and their families, especially those from low-SES backgrounds and minoritized populations.[11]

ASD providers were sparse in Michigan’s rural and low-income areas

At the time of this study, Michigan had about 9.86 million residents living mostly in urban (33.4%) and suburban (43.8%) areas, with 22.8% in rural areas. Even relative to their population, individuals in rural areas had fewer available ASD providers than those in suburban and urban neighborhoods. Of the 352 ASD providers assessed, about 36% were in urban areas, 48% in suburban areas, and 16% in rural areas. Notably, of Michigan’s 83 counties, 17 predominantly rural counties representing nearly 258,400 residents had no ASD providers.

The authors created an index of socioeconomic distress for neighborhood (i.e., census block groups) based on four variables: (1) proportion of residents aged 25 or older without a high school diploma, (2) proportion of unemployed adults aged 16 and above who were eligible to work, (3) proportion of single-parent families, and (4) proportion of households living below the federal poverty level. Results show that wealthier suburbs had good provider availability while fewer providers were available in poorer urban neighborhoods, particularly in the Metro Detroit area. Nearly 58% of urban populations in Michigan lived in low-SES areas at the time of this study while 62% of urban ASD service locations were found in high-SES areas.

Factors related to robust service availability are often overlooked

This research highlights a core challenge of ASD service provision—availability. Most low-SES urban neighborhoods struggle with limited access to ASD service providers. Rural areas are also frequently underserved. It is not surprising that fewer ASD services exist in rural areas and that rural families must travel further distances to access those services. However, the research team found that disparities in ASD service availability in rural areas were greater than would be expected by population density alone.

Most research investigating service availability for low-SES families seeking ASD-related services has focused on barriers to availability faced by those seeking treatment services (e.g., cost, transportation, limited flexibility in work schedules, low health literacy).[12] Simply put, autism services are less available for low-SES families compared to high-SES families. Urban ASD service deserts overlap areas that are also low-SES neighborhoods. As such, low-SES families seeking ASD services have fewer service options available and must travel farther to access those services than families living in higher-SES urban neighborhoods, even when the population densities are similar.

While addressing service gaps in urban and rural regions may be difficult (especially given the profit-driven nature of the healthcare industry), other options can help fill service gaps. These include meaningful engagement with state-level ASD advocacy groups; targeted, evidence-based informational outreach to communities more distant from provider offices; integration of ASD treatment services with behavioral health and primary care providers;[13] continued support for school-based health centers;[14] mobile autism clinics;[15] and expanded telehealth services.[16] Systems-level interventions to reduce ASD service disparities might include policies to encourage service providers to relocate or branch out to socioeconomically distressed and rural areas.

Throughout their lives, individuals with ASD tend to access services less frequently and receive lower-quality care compared with individuals with other disabilities.[17] Families of children with ASD also have greater difficulty accessing educational and healthcare services and have higher unmet service needs compared with families of children with other specialized health-care needs. Across the lifespan, disparities in treatment services can lead to lower health quality and social functioning outcomes for people with autism.

The challenges of ASD service deserts affecting low-SES and rural areas are closely linked with other healthcare challenges faced by people living in low-income and rural areas. All will benefit from proactive and equity-minded incentives and planning to broaden service availability and improve long-term health outcomes.

[1]Pickard, K.E., & Ingersoll, B.R. (2016). Quality versus quantity: The role of socioeconomic status on parent-reported service knowledge, service use, unmet service needs, and barriers to service use. Autism, 20(1), 106–115.

[2]Durkin, M.S., Maenner, M.J., Meaney, F.J., Levy, S.E., DiGuiseppi, C., Nicholas, J.S., Kirby, R.S., Pinto-Martin, J.A., & Schieve, L.A. (2010). Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a U.S. cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 5(7), Article e11551.

[3]Dawson, G. (2008). Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Psychopathology, 20(3), 775–803.

[4]Shattuck, P.T., Wagner, M., Narendorf, S., Sterzing, P., & Hensley, M. (2011). Post-high school service use among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(2), 141–146.

[5]Patten, E., Baranek, G.T., Watson, L.R., & Schultz, B. (2013). Child and family characteristics influencing intervention choices in autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28(3), 138–146.

[6]Williams, D.R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N.B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology, 35(4), 407–411.

[7]Murphy, M.A., & Ruble, L.A. (2012). A comparative study of rurality and urbanicity on access to and satisfaction with services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31(3), 3–11.

[8]Drahota, A., Sadler, R., Hippensteel, C., Ingersoll, B., & Bishop, L. (2020). Service deserts and service oases: Utilizing geographic information systems to evaluation service availability for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 24(8), 2008–2020.

[9]Steinbrenner, J.R., Hume, K., Odom, S.L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S.W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N.S., Yücesoy-Özkan, Ş., & Savage, M.N. (2020). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team.

[10]Levesque, J.F., Harris, M.F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centered access to health care: Conceptualizing access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, Article 18, (pg. 4).

[11]Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., & Kind, A.J.H. (2017). A scoping review of health disparities in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3380–3391.

[12]Pickard, K.E., & Ingersoll, B.R. (2016). Quality versus quantity: The role of socioeconomic status on parent-reported service knowledge, service use, unmet service needs, and barriers to service use. Autism, 20(1), 106–115.

[13]Mazurek, M.O., Brown, R., Curran, A., & Sohl, K. (2017). ECHO autism: A new model for training primary care providers in best-practice care for children with autism. Clinical Pediatrics, 56(3), 247–256.

[14]Kang-Yi, C.D., Locke, J., Marcus, S.C., Hadley, T.R., & Mandell, D.S. (2016). School-based behavioral health service use and expenditures for children with autism and children with other disorders. Psychiatric Services, 67(1), 101–106.

[15]Abrams, Z. (2018). Traveling treatments. Monitor on Psychology, 49(9), 46–52.

[16]Sutherland, R., Trembath, D., & Roberts, J. (2018). Telehealth and autism: A systematic search and review of the literature. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 324–336.

[17]Chiri, G., Warfield, M.E. (2012). Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(5), 1081–1091.

Categories

Child Development & Well-Being, Children, Health, Health Care, Inequality & Mobility, Inequality & Mobility General, Place, Spatial Mismatch