- Anna Walther

- September 2019

- Factsheet19

- Link to Factsheet-19-2019-Low-Wage-Work-WI (PDF)

Introduction

Wisconsin is a hard-working state: each age, race, and education demographic works more hours on average than their national counterparts.[1] While Wisconsin’s economy improved in the years following the Great Recession, this economic growth is just now translating into increased well-being for many low-wage workers and their families. Wage growth has been slow for jobs near the bottom of the income distribution and is only just beginning to return to the levels of the early 2000s. Meanwhile, government safety net programs may have been scaled back before low-income workers’ wages could catch up. Some evidence suggests that these factors may contribute to continued poverty and fewer returns to work for low-wage workers in Wisconsin.

More Than 20 Percent of Wisconsin Workers Are in Low-Wage Jobs

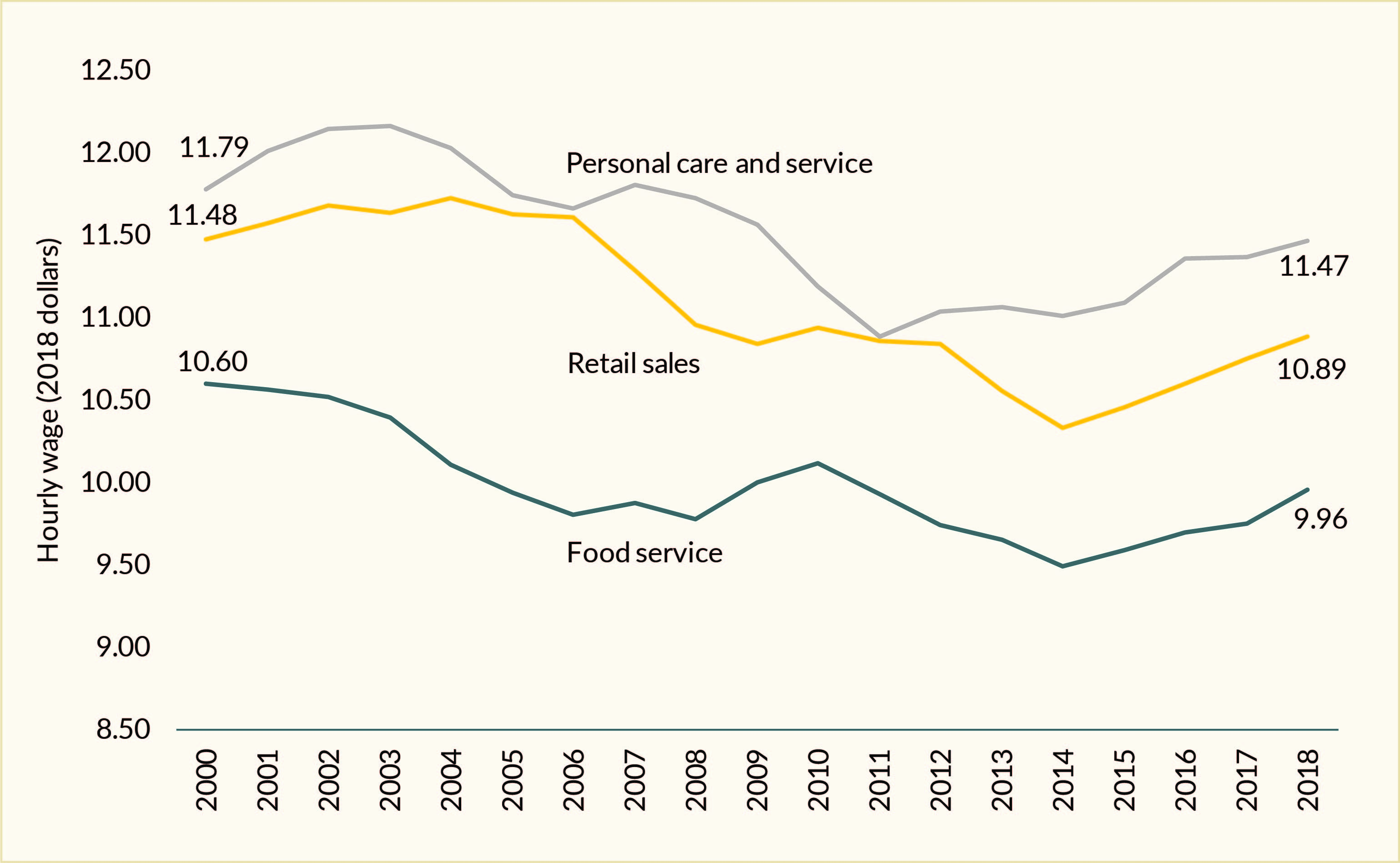

In 2018, about one in five Wisconsinites earned an hourly wage of less than $12.00 per hour. Many of the workers earning low wages provide critical services that are necessary for everyday life. Three major categories of these low-wage jobs in Wisconsin are food service, retail, and long-term health and personal care services. Table 1 shows the number of Wisconsin workers and median hourly wages for each of these categories. Nearly a quarter of a million Wisconsinites work in food preparation and service jobs: this includes waiters and waitresses, fast food staffers, and bartenders. The average food service worker earns wages well below what a family of four would need to stay above the federal poverty line ($25,100 in 2018). Long-term care aides—who provide invaluable care for those unable to take care of themselves—fared only slightly better: personal care and service workers earned a median hourly wage of $11.47 in 2018.[2] Wisconsin’s retail workers also earned wages below the poverty threshold for a family of four, earning an average hourly wage of $10.89. Although they comprise a large share of the state’s workforce, workers in these three job categories cannot on average lift a family of four above the poverty line working 40 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year.

| Table 1. Median wages in three large low-wage job categories in Wisconsin are not high enough to lift a family of four out of poverty. | |||

| Food service | Retail sales | Personal care and service | |

| Number of workers in 2018 | 245,820 | 81,160 | 117, 390 |

| Median wage in 2018 | $9.96 | $10.89 | $11.47 |

| Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Statistics data. | |||

Low-Wage Service Sector Jobs Have Not Kept Pace with The Costs of Living

Source: Occupational Labor Statistics data, Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010-2018.

Note: Adjusted for Inflation to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers Research Series (CPI-U-RS).

While Wisconsin’s economy added more than 233,000 jobs between 2011 and 2018 and the state’s unemployment rate fell to 2.9 percent in 2018—a historic low—growth in wages for low-wage service jobs has been slow at best.[3] The state has largely recovered from the 2008 to 2009 Great Recession, but economic growth has been concentrated at the top of the income distribution. Not only are median wages low in the largest lower-skill service sector jobs, but after adjusting for inflation, hourly wages remain slightly lower than they were at the turn of the century. As shown in Figure 1, inflation-adjusted median wages for three of the state’s largest low-wage service job categories dropped around the Great Recession and have been slow to recover. This slow recovery has negative implications for low-wage workers, who are facing declines in social safety net benefits and increases in costs of living such as rent, food, and transportation.[4]

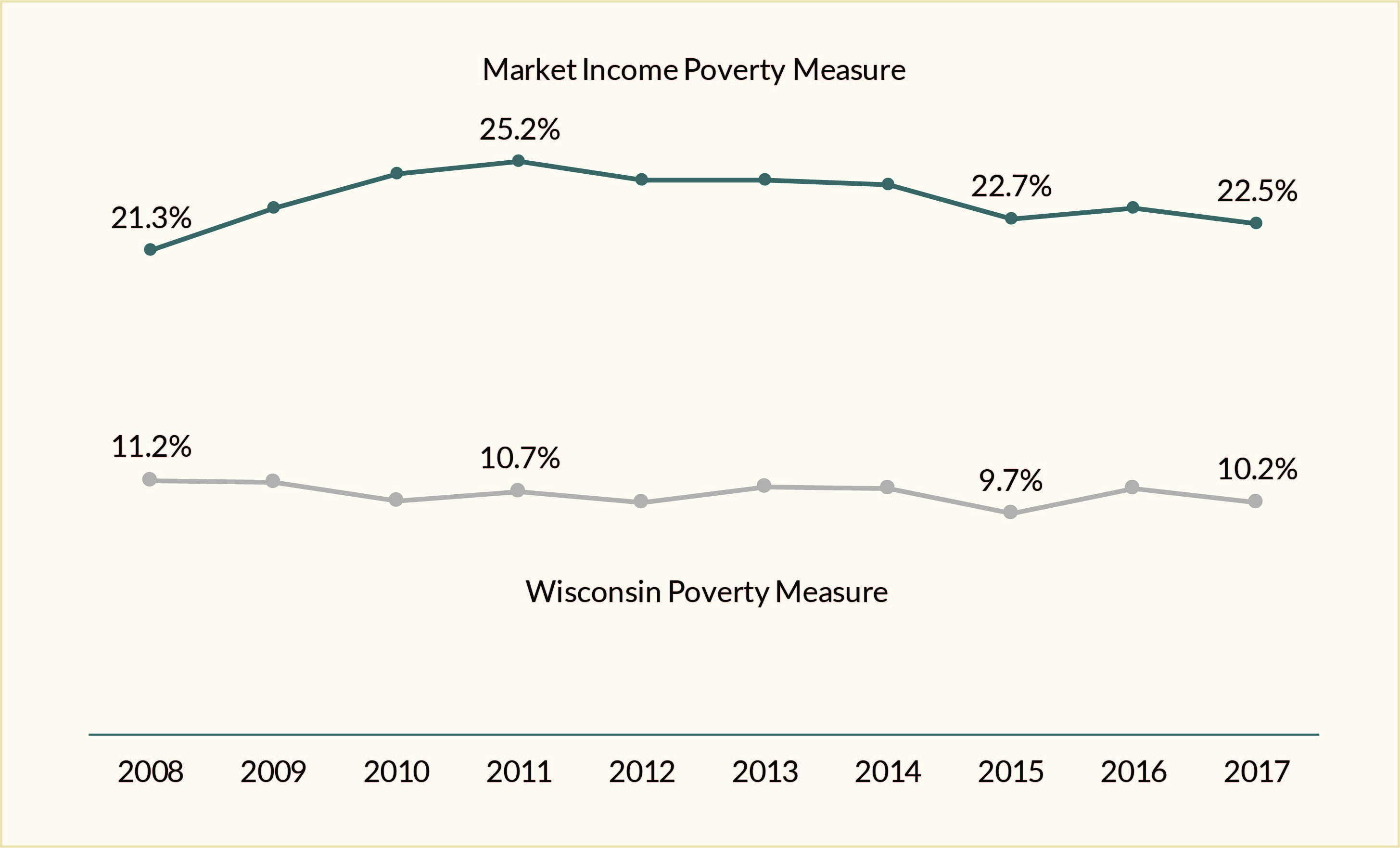

Poverty Has Increased Despite Growth in The Number of Jobs

Source: T. M. Smeeding and K. A Thornton. Wisconsin Poverty Report: Treading Water in 2017. Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison, June 2019.

Despite the state’s improving economy, evidence suggests that poverty in the state is stagnant, in part due to increasing costs of living, stagnant wages, and a safety net that is being scaled back. The Wisconsin Poverty Report, developed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Institute for Research on Poverty, produces two poverty measures, shown in Figure 2, that reflect Wisconsin-specific costs of living.[5] One measure, the Market-Income Poverty Measure, takes into account private earnings and reflects how successful wages and hours worked have been in keeping people out of poverty. As shown in the figure, this rate slowly fell from a peak of over 25 percent in 2011 down to 22.7 percent in 2015, crept back up to 23.2 percent in 2016, and then leveled off at 22.5 percent in 2017.[6] This suggests that even though there are more jobs in Wisconsin and more people working, wages alone are not doing as much to lift people out of poverty. A second measure, called the Wisconsin Poverty Measure, provides a more complete picture of the resources of Wisconsin households and, in addition to private earnings, includes the value of cash and noncash public benefits. As shown in Figure 2, this rate stayed mostly flat in the years following the Great Recession. Despite the growth in the economy, scaled back public benefits and decreasing returns to work may be preventing poverty levels from decreasing further.

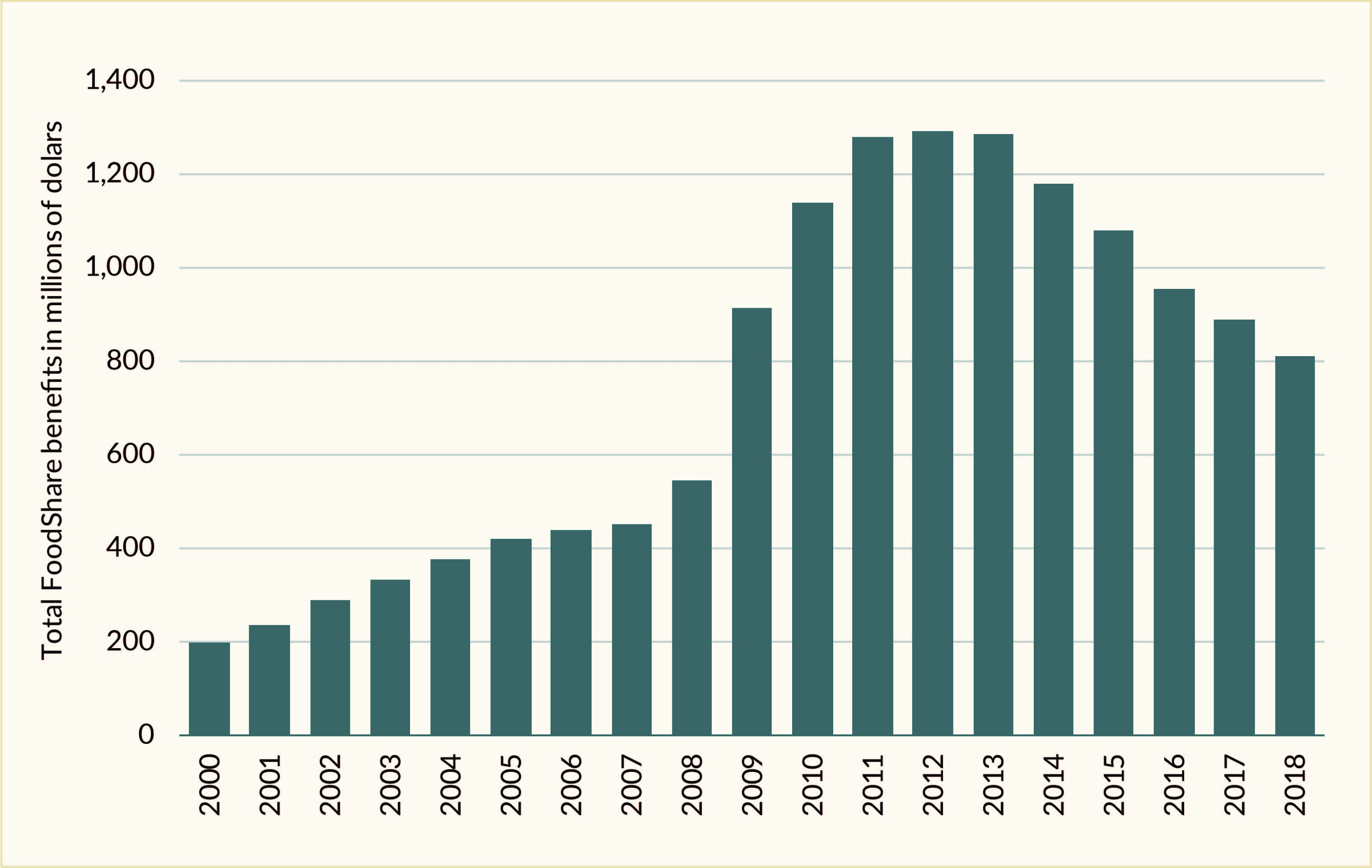

Low-Wage Workers May Be Pinched as Public Benefits Are Scaled Back

Source: Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Note: Adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars.

In the years following the Great Recession, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or FoodShare in Wisconsin) caseloads and overall benefits rose dramatically in Wisconsin, as shown in Figure 3, mirroring national trends.[7] This drove the Wisconsin Poverty Measure rate down, and helped many workers afford necessities when their wages didn’t cover all of their expenses. However, as the state recovered from the Great Recession, some families may have become worse off. After falling to 9.7 percent in 2015, the Wisconsin Poverty Measure rate (see Figure 2), rose to 10.8 percent in 2016 before falling to 10.2 percent in 2017. These increases from 2015’s rate reflect higher work-related and health care costs and a smaller impact from government anti-poverty programs like SNAP that helped mitigate poverty during the recession.[8] Recent policy changes may make it more difficult for low-wage workers to use government benefits to fill in the gaps.[9]

Conclusion

Despite the economic recovery from the Great Recession, many Wisconsin workers are still struggling to make ends meet. Recently, policymakers like Governor Evers have indicated that they want to increase the state’s $7.25 per hour minimum wage. Even a modest increase could offer meaningful positive impacts for low-wage Wisconsin workers as median hourly wages for many occupations in the state remain below $10 per hour. Other options that could help increase the returns to low-wage work include expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, investing in training programs for low-skilled workers, and increasing access to programs like SNAP that can help support Wisconsin families who struggle to get by despite their hard work.[10]

Endnotes

[1] L. Dresser, J. Rogers, E. Ubert, and A. Walther, The State of Working Wisconsin Report 2018. COWS, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2018.

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics.

[3] Dresser et al., State of Working Wisconsin.

[4] S. Baron. State of the States Report 2014: Local Momentum for National Change to Cut Poverty and Inequality. Center for American Progress Fund, December 2014; T. M. Smeeding and K. A Thornton. Wisconsin Poverty Report: Treading Water in 2017. Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison, June 2019.

[5] Smeeding and Thornton, Wisconsin Poverty Report.

[6] Smeeding and Thornton, Wisconsin Poverty Report.

[7] Smeeding and Thornton, Wisconsin Poverty Report.

[8] Smeeding and Thornton, Wisconsin Poverty Report.

[9] D. J. Hall, “Effects of Wisconsin’s Food Stamp Work Mandate Remain Opaque as Rules and Costs Expand,” WisCONTEXT. 2018; A. Brauer, Wisconsin Legislative Council Act Memo. 2017 Wisconsin Act 264 [January 2018 Special Session Assembly Bill 2]: FSET Participation for Able Bodied Adults. Vol. 3. Madison, WI: Wisconsin State Legislature, 2018.

[10] L. Dresser and K. Walker, “Equity in Apprenticeship: Manufacturing Pathways in Milwaukee,” COWS, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2018; E. Maag, “Tax Reform 2.0 Should Expand Childless EITC to Reduce Poverty,” Tax Policy Center, 2018; D. Rosenbaum, “Boosting SNAP Benefits Would Improve Diets of Low-Income Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2016.

This brief was supported by Cooperative Agreement number AE00103 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein should not be construed as representing the opinions or policy of any agency of the federal government.

This brief was supported by Cooperative Agreement number AE00103 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein should not be construed as representing the opinions or policy of any agency of the federal government.Categories

Economic Support, Employment, Inequality & Mobility, Inequality & Mobility General, Labor Market, Low-Wage Work, Poverty Measurement, Social Insurance Programs, State & Local Measures, Unemployment/Nonemployment